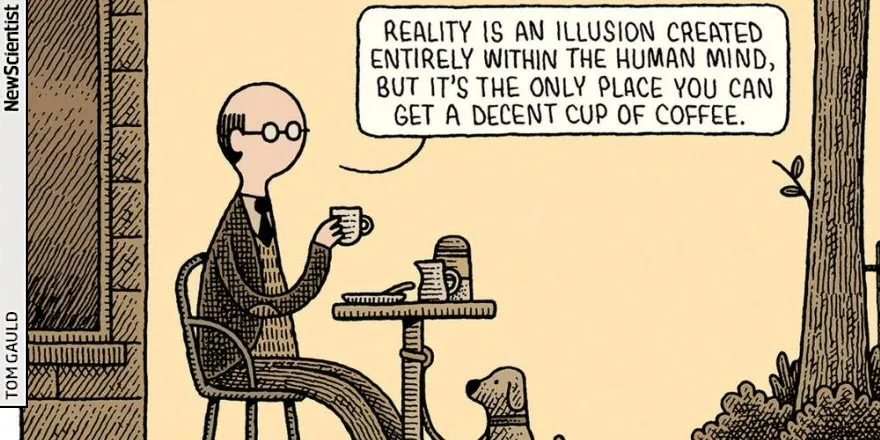

You have lots of ideas about how things are. In fact, that's how you make sense of the world.

Your brain creates a model of “how the world works” and uses this model to evaluate everything it perceives.

Having this model of the world often proves to be an invaluable asset (I'm sure you can imagine how useful this is). But it's also one of our biggest weaknesses.

As we further develop our model, we also increase our confidence in its accuracy.

Usually, this goes unnoticed. However, sometimes, an idea will come along that's so opposed to our model that we'll immediately dismiss it.

Let's look at an extreme example to show what I mean:

Imagine you're catching up with your old friend, and they bring up how they've joined a cult where they'll rule over everyone in the afterlife.

Chances are, your immediate response will be something less along the lines of “wow, sign me up!” and more along the lines of “what the hell are you smoking…”

In this scenario, most people would probably have a similar reaction, immediately discounting what their friend said as irrational (and I'm definitely not saying that this is a bad response).

This gives rise to an interesting line of questioning: how do we determine what's rational and irrational with such certainty?

I know this may not seem like the most interesting or consequential line of questioning right now, but I promise that it leads to many fruitful and unintuitive conclusions, so make sure to stick around if you're interested.

What do we mean by rational and irrational?

For the sake of productively talking about the concepts of rationality and irrationality, it's probably a good idea to briefly talk about what we are referring to with each term.

Google defines rational as a word that describes anything that is "based on or in accordance with reason or logic."

This is a pretty good definition, but it overlooks some important details about rationality.

For the sake of this discussion, we can talk about something rational as something that we deem to be true, where truth is an accurate representation of the way things are.

It's important not to lose sight of the fact that the purpose of truth is to get at the way that things actually are, and it is unnecessary to conflate other concepts like logic and science with truth (although they are certainly relevant).

If we define truth and rationality like this, then we can simply define irrationality as the lack of truth or the opposite of rationality.

How do we determine that something is irrational?

So what goes into the split-second decision that leads us to dismiss ideas as irrational so easily?

The key to this question lies in the way that we interpret rationality.

At the simplest level, we determine how reasonable something is based on how much it fits with our model of the world.

This statement may seem extremely controversial at first. After all, such a statement seemingly implies that what we believe to be rational is more grounded in what we think is true, rather than what is actually true, which is contradictory to the concept of rationality.

Because of how naturally opposed we are to this claim, it's much easier to talk about it with an analogy, which can help to point out some of the most important nuances of this topic.

The perfect analogy to illustrate this point (and also to draw many interesting conclusions from) is one that some of you may be familiar with: Plato's allegory of the cave.

The allegory of the cave

The allegory of the cave details the lives of a few prisoners who were chained up in a cave for their entire lives, unable to move. Their heads were pointed toward a cave wall and all they were able to see for their whole lives were the projections on the wall.

In the cave, there was a fire lit behind the prisoners, such that the light from the fire cast shadows on the wall in front of them.

Throughout the prisoners' lives, people would come through the cave casting different shadows onto the wall. This was their entire experience of life - they knew nothing besides the sounds they heard in the cave and the shadows on the wall.

Finally, one day, the captors decided to release one of the prisoners. This prisoner was freed from his chains and allowed out of the cave into the rest of the world.

At first, the prisoner was alarmed and overwhelmed by the novelty of the world. He couldn't make sense of everything and only recognized the reality in the shadows cast by objects.

But of course, over time his eyes started to adjust and he started to recognize all of the wonders and beauty of the world - he started to understand how much more there was to life than what he ever could have imagined.

Years later, after he had experienced the world, he decided to make a trip back to the cave to tell his friends about all his amazing discoveries.

He arrived at the cave and began to detail all of his experiences to his friends. He tried to explain how much more there was to the world than the shadows on the wall.

His friends had no idea what he was talking about. Even worse - they thought he had gone crazy.

After trying his best to explain to his friends, he gave up, realizing that there was no way for them to understand what he had seen, and he left the cave dismayed.

What's this all about?

This story might not seem particularly relevant yet. Cave, shadows, prisoner... what does any of this have to do with truth and rationality?

A standard cursory analysis of the allegory of the cave will tell us that the story is about how we are equivalent to the prisoners that remained in the cave, missing out on so much of the truth to the point where we can't even recognize it when its right in front of us.

It also points to the fact that there are so many things we don't know, but we can't even conceptualize them, so we don't think about them, and we suffer the consequences.

These are both good points, but we can go much deeper to pick out the core lessons that the allegory of the cave has to offer, and we can see how this relates to our original claim about how our perception of rationality is deeply influenced by what we believe.

We can't conceptualize what we haven't experienced

One of the most important concepts that the allegory of the cave brings light to is the idea that there are certain things that can't be explained with words.

In the case of the story, the prisoners trapped in the cave had lived a life only by experiencing shadows and thus were completely unable to understand anything that could exist outside of shadows when the released prisoner tried to explain it to them.

Clearly, this was not the fault of the released prisoner's explanation, but rather was a result of the fact that his experiences were so different from the prisoner's experiences that they could not even begin to imagine what he was talking about.

It's important to internalize how true what the released prisoner is saying is, and how crazy the prisoners believe it is. It doesn't even occur to them that he is talking about something they don't understand. Instead, their default response is to assume that he's gone crazy.

Why do they do this?

Because what the released prisoner is saying is fundamentally a description of an experience. And unique experiences cannot be conveyed in words.

I'm not talking about the experience of seeing the world from the top of a mountain and being at a loss for words, I'm talking about an experience so foreign to someone, that they cannot possibly understand it.

This statement has an important implication: if we only deem concepts that can be explained with words as rational, we will miss out on all of the truths that lie in unique experiences.

This all sounds great in theory, but so far I've only been talking about it in the hypothetical allegory of the cave.

However, by no means is it difficult to find examples of such unique experiences in our everyday lives that fit the same requirements.

Take, for example, your sense of sight. Since you're reading this, it's probably safe to assume that you can see.

However, there are people that have been blind for life and have no experience with sight. It would be completely impossible to even begin to explain to them what sight is like.

They have absolutely no way of conceptualizing the experience that all of us have when we see.

In the same way, all of the senses fit the description of experiences that cannot be explained with words.

However, although there are no rational grounds for explaining these phenomena (outside of trusting our own experiences), they are very much real.

My point here is that it is equally plausible that there are other such phenomenological experiences that we simply don't have the ability to understand without experience.

However, just because we haven't had these experiences, doesn't mean that no one has. There are plenty of people who claim to have had incredible and unexplainable experiences through media like meditation, psychedelics, and many others.

Imagine if these people were actually describing real experiences (I'm not suggesting that you just blindly trust them, but I am suggesting that it may be worth being open-minded to some). Even if they were, no one would believe them, and they would be dismissed as crazy in conventional circles.

This is an unfortunate reality about how we perceive the truth. Regardless of if someone is actually describing the truth or not, we judge what is true based on what we are able to conceptualize from our limited experience.

I think it's reasonable to suggest that there is so much truth that we are unable to conceptualize, and without direct experience, we have no way of justifying it rationally, so we take it for irrationality and dismiss it.

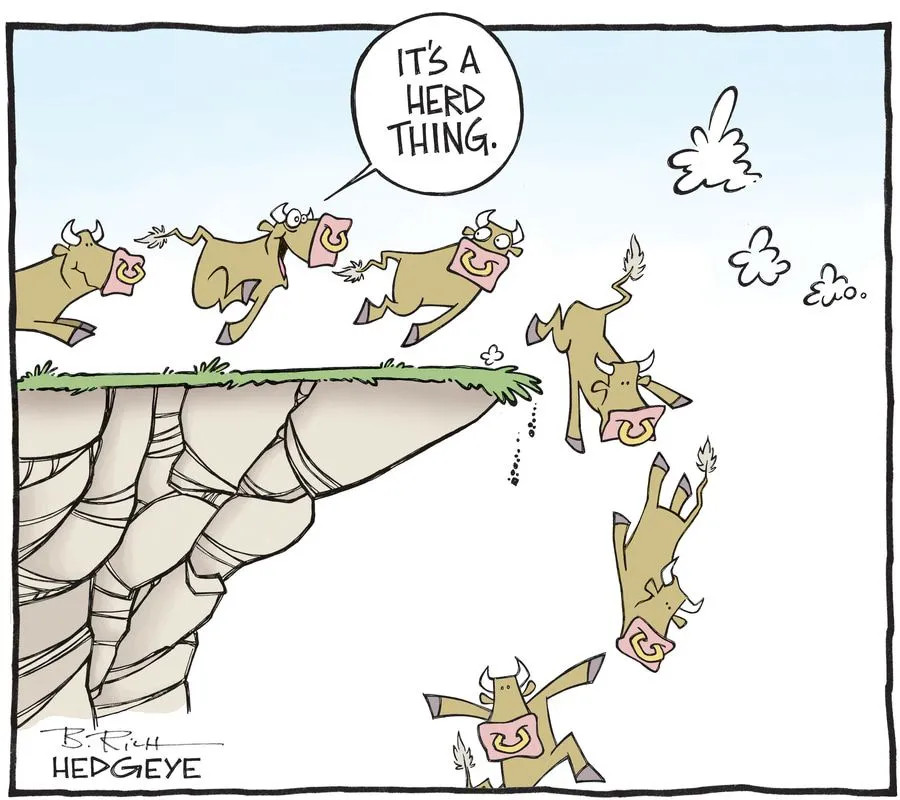

We put blind trust in numbers

You may have identified what appears to be an inconsistency in what I just described. I brought up two comparisons in the previous section: I compared the blind minority to the unblind majority, and I compared the minority who have had unique experiences through media like psychedelics and meditation to the majority of society who have not.

However, there is a clear difference between both of these scenarios.

In the first case, blind people typically believe the unblind majority, despite the fact that they cannot understand what sight is. Conversely, in the case of the person who has had a unique experience, the majority tends to be skeptical of the minority.

It may then seem reasonable to suggest that the experience of sight is just much more believable and true than the meditative or psychedelic experience (which we are naturally more skeptical of), and this is what causes that difference in belief.

However, I want to bring your attention to an important difference between the two scenarios above.

In the case of the blind, the majority has an experience that the minority cannot understand. However, in the latter case, the minority has an experience that the majority cannot understand.

This difference in numbers accounts for the difference in people's predisposition to deem an experience truthful or crazy and points to the fact that we often put blind trust in numbers.

We can understand this more clearly by looking deeper at the above examples.

In the case of the blind, we might be curious to ask why they believe that there is something called sight that exists, but they just have not experienced it. The most likely answer is that since so many people have told them that there is something called sight, they believe that it's true.

But it's important to note that there is still no rational explanation given to them that points to the existence of such a phenomenological experience that they have not experienced. However, if you mistake rationality to be believing in things that can be logically explained, then you would think that the blind are irrational by believing that sight exists.

Yet you know that sight is a real thing. So by that logic, rationality predicated on explanation alone would actually not point you toward the truth. This is why it's so important to expand our view of rationality beyond just the explainable.

Meanwhile, if we look at the example of people who have supposedly attained unique experiences through unconventional means, we are met with the exact same scenario.

There are no rational means to explain their experience. So does this mean that we should discount it as false? As we saw above, it's a flawed line of reasoning to require rational explanations for things in order to consider them true, specifically in the case of unique experiences. So maybe we ought to reconsider how we perceive some of these people and their experiences.

To conclude this section, I'd like to leave you with some interesting thought experiments which may help to illustrate my point here:

- Imagine what would happen if no one decided to mention to a blind person that there was something called sight for their whole lives. Then one day, someone decided to try to explain to the blind person that something called sight existed. How would the blind person respond?

- Now imagine that instead of the minority of people being blind, the majority of people were blind, and there were only a select few people in the world that could see. Think about what the world would be like, and how sight would be treated. Would sight be accepted for what it is? Could it be considered crazy or delusional?

We conflate our own perspective of reality with reality itself

It's curious that in all of the above examples, our natural inclination is to reject seemingly crazy beliefs with such certainty. After all, how can we be so sure that we are not in fact the people who are wrong, and that the people saying things that sound irrational are right.

The answer to this question points to an important truth about how we perceive reality and the world: we conflate our own beliefs about reality with reality itself.

What I mean by this is that we subconsciously think that our perspective of reality is the truth and that we've got it all figured out. This effect often gets magnified as we get older and more solidified in our beliefs. Because of this, the very idea that there could be more to reality beyond what we have experienced seems implausible.

We are so certain that we have reality figured out that we immediately take any suggestion that doesn't fit within our perspective of reality as crazy, rather than taking it into consideration.

In the allegory of the cave, the prisoners are so certain that their own experience of life is the most real one that they so easily reject the released prisoner's explanation, and genuinely believe that they are in the right.

As you can probably tell, this is a huge fallacy. The belief that we have it all figured out points us away from some of the most interesting truths that the world has to offer (as it did for the prisoners, who didn't even know how much they were missing out on that went on in the outside world).

Unfortunately, when we are overly certain about our own beliefs about the world, it's not only bad for us. In fact, this kind of certainty in your own world views not only leads to distrust of people who are speaking the truth, but it is also the source of much of the conflict and disagreement in the world.

For the sake of moving on, I won't go into all of the detail that that topic has to offer (it could be its own post), but its easy to recognize the significance of that fact.

This is not a hypothetical

All of the points that I've made here can be understood from a purely rational perspective (ie you read my explanation, and you agree with how I got from my evidence to my conclusions).

However, in order to actually get most of the value from these observations, it's important to actually internalize how these phenomena that we have not yet experienced are not hypothetical, but very much exist in the real world.

This discussion has particular relevance today as an increasing number of fields like psychedelics and meditation are gaining popularity - even though they aren't yet fully understood by science.

Because of this, people are often extremely skeptical of them.

However, these two areas are arguably some of the most important in personal psychological development and in understanding consciousness and existence as well.

This is exactly what prompted me to write this post — I often see skepticism around these topics, for good reason, and yet they have so much to offer if only people were more open-minded to them.

Like these topics, there are many more of import that are worth exploring. But for now, let's get back to our discussion and sum everything up.

The truth in the seemingly irrational

So now that we've made all of these observations about the truth and the nature of our rationality, let's try to tie it together into something that we can better make sense of.

To summarize the most important points that we've made so far:

- There are things that we can't explain with words alone, and we can't conceptualize them without experiencing them first.

- If we only believe that things that can be explained with words are rational, then we will miss out on some of the most significant truths that deal with such experiences.

- It is plausible (and probable) to suggest that there are an overwhelming amount of such experiences that we have not yet experienced, and thus cannot understand.

- Regardless of if someone is actually describing the truth or not, we judge what is true based on what we are able to conceptualize from our limited experience.

- When it comes to things that can't be explained purely with words, we tend to default to believing in the majority perspective on these beliefs (regardless of the truth of the majority's perspective).

- We conflate our own perspective of reality with reality itself, and as a result, we reject truths that lie outside of our perspective of reality with certainty.

We can condense all of this into one more important point that seems to jump out from these points: some of the most significant and profound truths about reality are those that cannot be understood without experiencing them.

In fact, the fact that we haven't experienced them is almost directly correlated with their significance; the fact that these truths are experiences is what makes them so powerful, but it's also what makes them inaccessible.

Take for example the experience of sight. The experience of the senses is one of the most incredible things about our experience of life that we don't understand, and yet it is completely inaccessible to those who have not experienced it.

Imagine how powerful an experience of sight would be to someone who was blind, or how an experience of hearing would be to someone who was deaf. The significance of these experiences is not even properly quantified with words.

Thus, it's in our own best interest to try to understand and be open-minded to these perspectives, in the hopes that we may one day be able to experience them ourselves.

Some final thoughts

I often find that this topic is an important precursor to many other explorations of philosophy and consciousness — which is why I've written about it here.

If you liked this post, check out some of my others here